#3 - Sensibility - The Enigma of Susan Pt. 2

#3 - Patience of Storytelling - The Enigma of Susan Pt. 2

#3 - Cinematic Tangibility - The Enigma of Susan Pt. 2

My middling enthusiasm for Salem's Lot withstanding, the too-inoffensive miniseries still has profundity in it yet, most clearly found in its quiet but very consistent sense of character. This has a way of sneaking up on you, as it must accumulate through the film's episodic structure made up of many miniature character snippets, of many, many short scenes juggled and interweaved, all while this acuteness of character-building exists more as subtext than text, communicated through bits of the most succinct interaction and floating free amidst the action narrative rather than motivating it itself or being of any driving impact on it.

Who remembers those scenes going towards such subplots as Susan, in-and-out of New York (and the film itself) as she leaves Salem's Lot for a New York job interview? How about the hapless guest appearances of the Mark Petrie parents, who fail to connect to their unique child before being unceremoniously murdered? The equally taciturn portrayal of Susan's own depth-bereft parents? (An early scene between Susan and her mother: "What's his book about?" "Oh... it's about two men." Mother stops in her tracks: "Not one of those!") One rather large character strand that seems to be easily neglected is the uninspiring competence of the town's sheriff (played by Kenneth McMillan), whose investigation into the strange events of his town is shown to be pursued ably, but ultimately incompletely, as his story ends with him hitting the road, leaving the "outsiders" and "odd ducks" of the film to battle Straker and Barlow.

These subplots contribute greatly to the film, lending it its true layers and deepening its fleeting intimations about small-town minds, fates, and inner characters. They progress each their little bit, but the character that gets the most mileage out of the film's subtextual mad dash is, of course, Susan, the female lead. First let's take into consideration her part in the total context of the film: her unmistakeably passive role in the story; her precocious sense of independence and liberation, yet her being seemingly done in by her small-town temperateness; the viability of her escape to New York, since the vampires do not come anywhere near her or her family throughout the entire build up of the film (only for her to end up walking straight into the Marsten house), an advantage thoroughly disposed of for the fact she does not escape.

Shadow play: think Dreyer, Murnau, Tourneur, (Coppola): the tell-tale sign of an artist of the Uncanny.

A decision to leave.

An errant gust of wind... catches her attention.

A decision refuted by unknowable forces, or unseen fortunes. She returns to the camera she walked away from.

Whether it was a gust of wind or the rustling of the boy's movements among the brush, we never are to know for sure. As it is presented, it is both, as well as the forces of the Marsten House, the play of Fate, the whispered edict of a deity, etc.

The ambiguity (or, alternatively, the proliferation of possibility) respected is the essence of the uncanny.

Hooper's use of the edges of the frame, in ways so formally tied to his rigorous sense of

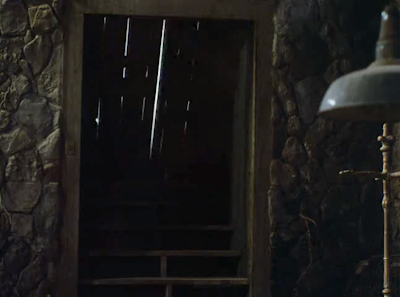

interlocking frames,

interlocking spaces,

interlocking mise en scene (mise en scene = frame and space as an idea)

Here, the camera's previously ultra-controlled frame, seemingly existing solely to draw Susan toward it (toward the house), not just once but twice... is suddenly broken, in order to introduce a wide shot of the hill she is about to climb, as she strikingly enters the frame, a lowly human before it.

More shadow play from Hooper:

From shadow, to - with a camera flourish - flesh.

Susan and Mark are entering a natural Gothic: the Arcadian world of fear, where the primordial element

retained in a rural land, an old house, and a bright sun carries a suffusion of oppressiveness in their untouched, untamed quality. In the profound uncanny, Nature is one with the terror. It is present in the play of the sun and its creation of shadows:

the house that makes time go faster, clouds moving like cars and the sun

going in and out like headlights (Susan looking at the house, above). The great metaphysics of the

shadow. When the danger is omnipresent, any shadow is an omen of death -

even Mark's own, which Hooper introduces a shot with (Mark takes to the lock, above), his shadow a

heroic, stealth bust... but still a shadow nonetheless: a reminder of mortality,

his body a mere middleman to the obliteration of particles and the sun. The fact Hooper's shot flourishes the distinction between the shadow and the flesh-and-blood hands that swing into the frame makes it clear Hooper knows the distinction he makes, of the vital body versus a shadow's absence. Simply these two moments of naturalistic, sun-kissed shadow play in the film go a long way to carry

this overlong, talky "talkie film" to the echelons of Murnau's Nosferatu and Dreyer's Vampyr, two super condensed and elemental films about life and death -- throughout his film, Hooper fights all the commercial "talking," but many sequences, like this one here, get frightfully close to silent cinema.

The Scaling. (A steep climb to Doom.)

Hooper seems to direct her to scale this hill as if it took the

mental and physical effort of Everest. Throughout the sequence,

Bedelia performs her character as if as clumsily petrified as possible.

She gawks at the sight of Mark with her lips like dead fish, then

climbs this hill like a

scurrying rat (in the lore of vampires, rats and humans are one and the

same, unwitting and pitiful carriers of death). Hooper aids this moment

with a camera movement that rolls back along the curve of the hill,

keeping in pace with Bedelia as she also traverses the curve of the

ground. Created is a striking optical parallax between the foreground

ground, Bedelia the rat moving in middle, and the road to escape she is

now leaving behind descending into the frame in the far and increasing background.

A decisive POV shot:

(Of Mark just finishing removing the chain and venturing inside.)

This entire sequence, as we've been seeing and which we will further see, is made up of shots of Susan traversing the frame -- always along an axis of depth in relation to the camera.

The sequence is about Susan's irreconcilable stream of decisions and movements leading her to the house, and so in the visual design is reflected a rigorous repetition of Susan walking towards and then past the camera, or near then away - but always along the z-axis perpendicular to the x- and y-axis of the camera frame.

The depth axis comes to represent Susan's physical journey - a journey of decision-making and fate-entrapping and an inextricable linearity - and also Hooper's allegorical camera of directionality, formally following this linearity (a sense of the "symbolic directional" and directional flow in his staging and mise en scene being so often - and already in so many of the scenes that have been already gotten to in this blog - a main source of formalist meaning in his scenecraft).

An extraordinarily dynamic and exciting shot literally picks up her motion:

She enters into the frame: an active, heroically-motivated figure.

The camera begins totally still.

If the direction the camera is looking in the previous shot of her climbing (the camera looking towards the road and town) is North, we are now looking East. The jump from the longitudinal axis to the latitudinal is striking, asserting this space as one existing in all directions, one with a profile in which to enter into. Susan's own profile enters the shot - joining that of the landscape - as owner/current occupant of this new, activated chunk of space we are now privy to see. Also asserted in Hooper's flowing sequence is Susan's sense of "necessity" in following Mark, her "owning" of her space and her actions being the fatefulness of this sense of necessity in retrieving the child. It is a major part of this beat, and a major part of Hooper's highly deliberate shot sequence.

Susan is either taking heroic action or lost in the cascade of action fated to her by the confusion of circumstances. Either way, Hooper's composes this sequence in sublime cascades of moving shots, making it artistically and formally and profoundly clear she is more and more passing a point of no return.

This

point of no return is essentially cemented when Susan's entrance into this shot

musically, dynamically cues the start of a camera motion: an orbital

around the linear-moving Susan, circling her as she continues forward, as if drawn by something - not the camera, but definitely in collusion with the camera. The camera knows what is happening: that she is a moth being drawn to a flame. (Yet the uncanny complexity remains: the draw is actually nothing sinister, just her sense of human obligation to concern herself about the boy. But then, is there anything more sinister than just being at the wrong/right place

at the wrong/right time? What is more sinister than fate, even when disguised in rationality?)

The point of no return is cemented with a return to the z-axis, surely not forgotten... Hooper figures it out so that it is brought back without need of a cut:

(Susan ends up in the foreground again, and so walks away from the camera in venturing forth -- into an all-new depth that takes her past even the sight of the camera)

(Susan ends up in the foreground again, and so walks away from the camera in venturing forth -- into an all-new depth that takes her past even the sight of the camera)

#3 - Cascade - The Enigma of Susan Pt. 2

Again drawn towards the camera, her stop at her mark near the lens (looking at that which lies before her: the camera-path) cues in harmonious instance another beckoning occurrence.

Another phantom breeze. But inside...

There is the sound of a wooden door slamming shut. The cellar door: it, of course, was left open behind her. Susan, startled, whirls around:

Perhaps a mocking reminder of escape, for she certainly does not register its foreboding:

that this literal "slamming shut" in her face the possibility of escape

should really have caused her to go bolting back the way she came from.

As if in musical accord, as the door behind her slams shut on the wind's volition, the door before her creaks open on its very own.

Hooper's camera configures itself in a very disciplined line of axis - Susan's line of axis, of her increasingly more inexorable linear path forward. In the camera's being always before or behind her, it manifests the path she takes. Here again he's allegorized with cinema styling the linear push of fate, the directional vectors of every decision we make and the stepping stones of every little thing that pushes us towards that decision. That these circumstances here take on a hint of the predatory supernatural is less important than the fact of its being couched in the natural and banal: the uncanny.

Gusts of wind, open doors forgot, rickety houses, and the perfect timing of coincidence.

And, along that great z-axis, she walks away from the camera and into the belly of the Marsten house.

* * *

No comments:

Post a Comment